FORA.tv Video player

Saturday 23 June 2007

Wednesday 20 June 2007

Should the USA continue the Cuban trade boycott?

To set the background for my reasoning behind one aspect of the answer in the affirmative would be to use the sanction/embargo policy setup in Iraq during Saddam Hussein's period of rule as a parallel. Many media outlets have of late, been promoting the idea that the USA should rescind their policy of embargo on Cuba for the good of the Cuban people. I will show in this paper, that whether there is an embargo or not, the unfortunate situation of Cuba's people will only change, when Castro and his minions are out of power or they change their policies.

For example, BEFORE the sanctions were imposed on Iraq, millions of Iraqi citizens were paying a massive economic and humanitarian price under Saddam's brutal dictatorship, not to mention all the while, he was building billion dollar palaces throughout Iraq.

Furthermore, AFTER the sanctions were imposed, millions of Iraqi citizens were paying a massive economic and humanitarian cost under his brutal dictatorship, not to mention all the while, he continued building billion dollar palaces throughout Iraq. However this time, instead of continued international outrage toward Saddam and his domestic policies, the outrage was pointed at the coalition of states supporting the sanctions, especially the USA. The sanctions in the short term did not change Saddam Hussein's lifestyle very much, but in the long run, weakened his ability to rule domestically and for the most part allowed the coalition to easily achieve their initial goals in both wars because of his lack of support at home.

OK, now on to Cuba. Many people are presently blaming the USA, and its Cuban embargo policies, for all of the social ills and economic hardships that the Cuban people are experiencing. In a similar situation as mentioned above with Iraq, when Castro was receiving his annual welfare cheque from the motherland (the former USSR), in the amount of $4.5 billion per year, his people continued to suffer as before, all the while, he continued to live a life of extreme luxury. Fast forward to the present, the Soviet Union no longer exists and Fidel's dole cheque is non-existent, BUT Fidel still lives a life of luxury, all the while his people go without.

The embargo is slowly working, it shows the Cuban people that the USA will stand behind its threats (ie. embargo) toward their dictator and gives them the assurance that we will at least stand firm this time, no matter what it takes.

Until the Cuban government allows the people the economic and political reforms they deserve, the embargo should stand.

For example, BEFORE the sanctions were imposed on Iraq, millions of Iraqi citizens were paying a massive economic and humanitarian price under Saddam's brutal dictatorship, not to mention all the while, he was building billion dollar palaces throughout Iraq.

Furthermore, AFTER the sanctions were imposed, millions of Iraqi citizens were paying a massive economic and humanitarian cost under his brutal dictatorship, not to mention all the while, he continued building billion dollar palaces throughout Iraq. However this time, instead of continued international outrage toward Saddam and his domestic policies, the outrage was pointed at the coalition of states supporting the sanctions, especially the USA. The sanctions in the short term did not change Saddam Hussein's lifestyle very much, but in the long run, weakened his ability to rule domestically and for the most part allowed the coalition to easily achieve their initial goals in both wars because of his lack of support at home.

OK, now on to Cuba. Many people are presently blaming the USA, and its Cuban embargo policies, for all of the social ills and economic hardships that the Cuban people are experiencing. In a similar situation as mentioned above with Iraq, when Castro was receiving his annual welfare cheque from the motherland (the former USSR), in the amount of $4.5 billion per year, his people continued to suffer as before, all the while, he continued to live a life of extreme luxury. Fast forward to the present, the Soviet Union no longer exists and Fidel's dole cheque is non-existent, BUT Fidel still lives a life of luxury, all the while his people go without.

The embargo is slowly working, it shows the Cuban people that the USA will stand behind its threats (ie. embargo) toward their dictator and gives them the assurance that we will at least stand firm this time, no matter what it takes.

Until the Cuban government allows the people the economic and political reforms they deserve, the embargo should stand.

Sunday 10 June 2007

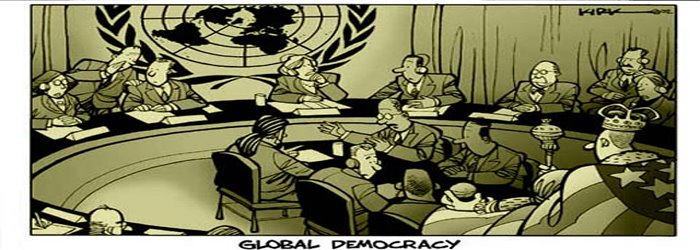

Is Major War between Industrialised Democracies Obsolete Today?

The question ‘Is major war between industrialised democracies obsolete today?’

This could be considered one of the most important questions of our time. Consequently, if there is a working formula or theory that will answer this question in the affirmative, it could provide like minded nations of the world and their leaders a resource, coupled with the motivation and governance necessary to share their combined knowledge and strength (using other successful states as their examples and providing justification) as a model to empower those not presently participating in democracy to join them with confidence and authority in uniting with the community of non-belligerent states. If taken to its end, it could inevitably go a long way towards eradicating war from the face of the earth.

The object of this report will be to support the theory that major war has become obsolete, while explaining the key terms in context to the question presented, and use historical events and information from experts, as a foundation to support this conclusion.

In order to build a foundation for the above assertion and provide cognizant evidence in support of this declaration, it will be necessary to define the critical aspects of the usage of particular verbiage contained in the initial question.

First-of-all, an ‘Industrialised Nation’, will be considered as a member of the ‘G8’, or ‘First World’ democracy, and for the purposes of brevity and example will include, as defined by the Council on Foreign Relations as; the United States of America, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, Canada and Russia[1]. The preceding states will be the focus of this report.

Secondly, Democracy or ‘Liberal Democracy’ in its broadest sense will be, for the most part, defined as states since 1945 that have the following criteria: (1) a government by the people, either directly or through elected representatives; (2) Modern, including a Universal Franchise, Secret Ballot, and Regular and Competitive Elections; (3) Liberal, Electoral, including Freedom of Speech, Religion, association and Rule by Law; (4) Historical, at least 2/3 of the adult male population can vote; (5) Competitive Elections, for Legislature and Executive and (5), at least one Transfer of Power.[2]

Thirdly, in an attempt to keep things direct and to the point for the purposes of this particular paper, one of Clausewitz’s definitions of war will be used in context to the essay question, namely, “War is nothing but a duel on an extensive scale.”[3]

Therefore, why is major war obsolete, or out of date, today? To answer this question, three situations will be looked at as support for the answer to the question. Firstly, democracies do not fight each other. Secondly, democratic states that are economically dependant upon one another do not go to war, and finally, democratic states that are ideologically bound by norms and institutions work together rather than fight one another.

In support of the first assumption that democracies do not fight each other, a quote from President Bill Clinton in his 1994 State of the Union address seems fitting, “Democracies do not attack each other…ultimately the best strategy to insure our security and to build a durable peace is to support the advance of democracy elsewhere.”[4] Since the end of World War II, and especially the fall of communism, democracy has taken hold all over the globe. For example, as of 2004, there were over one hundred democracies in the world.[5] Since there is extensive evidence to support the theory that democracies do not go to war with one another, and since the trend for states throughout the world since WWII to move towards democracy has dramatically increased, the probability of war between democracies will by default become more obsolete, or out of date as more and more non-democracies join the community of democratic states throughout the world.

Another explanation to support the conclusion supporting the democratic peace theory needs to be explored here. To quote John M. Owen, who explains two key theories of democratic peace, and why they work,

Structural accounts attribute the democratic peace to the institutional constraints within democracies. Chief executives in democracies must gain approval for war from cabinet member or legislatures, and ultimately from the electorate. Normative theory (italics added) locates the cause of the democratic peace in the ideas or norms held by democracies. Democracies believe it would be unjust or imprudent to fight one another. They practice the norm of compromise with each other that works so well within their own borders.[6]

In a democracy, the will of the people is paramount. Free citizens will naturally not vote

for war because they will not only be bearing the economic cost, through taxation, etc., they will be sending their own children to fight the actual battle.[7] In other words the cost is too high. Therefore, if all states in the world were democratic, people would vote to not fight, and thus war would become obsolete. Although not within the scope of this report, it is worth briefly mentioning that although there is strong evidence supporting peace between democracies, there is also a progressive philosophy, which theorises that as non-democratic states apply democratic ideals into their respective systems and as democratic peace initiatives mature, war between liberal states and illiberal ones become less likely as well. MacMillan elaborates on this theorem. He states, “…the balance of evidence and argument supports a shift from the conventional ‘separate democratic peace’ position that liberal states are peace prone only in relations with other liberal states to the view that they are also more peace prone in relations with non-liberal states than usually thought.”[8]

Secondly, democratic states that are economically dependent upon one another do not go to war. In speaking about perpetual peace as it relates to international law, Kant says, “The spirit of commerce, which is incompatible with war, sooner or later gains the upper hand in every state.”[9] Therefore, democracy inherently encourages an entrepreneurial spirit, which in the end, results in strong economies, full treasuries and economic stability, increasing the chance for even more stability as time goes on.[10] With the increased receipts going into a governments treasury, it is able to fund programs, build infrastructures, strengthen education, health care, and welfare, which will continue to help move a society even further away from a desire for war, because the society is content to maintain this status quo and do nothing that would risk upsetting it. In quoting Dr. Bhumitra Chakma, “According to Plato, war is less likely where the population is cohesive and enjoy a moderate level of prosperity.” He goes on to say, “wealthy masses are satisfied with the status quo (hence war is less likely).”[11] The need for war to secure economic prosperity and stability, especially within the context of the industrialised democracies, is not necessary and therefore the combination of liberal democratic ideals and economic growth within democracies over time will make war obsolete within the participating regimes.

And thirdly, democratic states that are ideologically bound by norms and institutions work together, for the most part, rather than fight one another. Speaking of the moral strength democracies gain by banning together in what he calls a ‘federation’, Kant states,

We have seen that a federation of states, which has for its sole purpose the maintenance of peace, is the only juridical condition compatible with the freedom of the several states. Therefore the harmony of politics with morals is possible only in a federative alliance, and the latter is necessary and given a priori by the principle of right. [12]

Incorporating Kant’s federation of states idea with economic interdependence, it has been shown that as economies in and between democratic states become more and more interdependent, the likelihood of war between these states is reduced dramatically. For example, institutions such as NAFTA and the EU have increased economic ties through their alliances and because of this, the likelihood of major war between even historical enemies such as France and Germany seems to have been eliminated. In an article written in the Journal of Peace Research, by John Macmillan, quoting Russet and O’Neal, they state,

The inter-relationships between democratic states, economic interactions and membership of international organisations can generate ‘virtuous circles’ that lead to greater levels of peace in international relations…they also find that international trade and membership in international organizations correlate positively with the probability of a state being at peace.[13]

As with many theories and ideas, there are always unforeseen possibilities or circumstances that can be categorized as exceptions to the rule. One of these possibilities needs to be explained at this point, and that is what Owen calls ‘perception’. In other words, even though a state considers or calls itself a liberal democracy, for example, doesn’t necessarily mean that other states believe the same. Owen states concerning the importance of perceptions,

That a state has enlightened citizens and liberal-democratic institutions, however, is not sufficient for it to belong to the democratic peace: if its peer states do not believe it is a liberal democracy, they will not treat it as one…for the liberal mechanism to prevent a liberal democracy from going to war against a foreign state, liberals must consider the foreign state a liberal democracy.[14]

An example of a state that could fall into this category at present is Russia. A lecture given by Dr. Jose M. Magone points out several factors that could cause one liberal democracy to question another liberal democracies level of ‘true’ liberal democratisation. In his conclusion, he gives five examples that show this, namely; Russia has experienced a turbulent transition to democracy, its autocratic past is still affecting the politics of Russia, and it has a strong presidential system with tendencies towards abuse, weak political parties, some of them very close to power and a fragile economy, in spite of recent spectacular growth.[15]

Because industrialised democracies have so much more to lose than gain by getting involved in a major war with one another in most circumstances, not to mention the great potential for human and economic loss, the likelihood of war between them is very low. For example, between 1952 and 1980 countries throughout the world that were considered democracies engaged in war with one another a total of zero times.[16]

In conclusion, the reasons industrial democracies do not fight wars with each other is because they encourage free trade with one another therefore becoming economically dependant upon one another and by their very nature as democracies see each another as partners that are ideologically bound by norms and institutions that are common in their political and cultural environments. It must also be noted that the very fact that the United States of America, with its military hegemonic might and superpower status, is a great help in forwarding and supporting the worlds move to democracy. With its society firmly behind the American idea that liberal democracy needs to be spread throughout the world, other democratic states everywhere will have the confidence and proxy-authority to do the same. Colin S. Gray, in The Making of Strategy says,

American society is deeply convinced that the world is destined to be governed by the precepts of American liberal democracy. Some influential Americans have taken the Soviet collapse as proof of the superiority of American ideas on good governance and enlightened economics over those of the forces of darkness and evil.[17]

With many new developing democracies maturing throughout the world at present, the future for peace could be said to have never been better than at this moment in time. As stated in this paper, as long as these states follow the example of true liberal democracy and apply its ideals of economic interdependence, and ideologically bind themselves together by implementing established democratic norms and institutions, eventual worldwide peace may be within reach.

In the spirit of the Kantian philosophy, freedom in all its forms may be the only sure way to secure long-term peace and security in a world that seems to be longing for more of it.

Anson D. Bentley

Bibliography

BBC News, Do Democracies Fight Each Other? -

http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk/mpapps/pagetools/print/news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/4017305.stm%20accessed%2030%20March%202007

Clausewitz, C., On War (Ware, Hertfordshire, Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1997)

“Excerpts from President Clintons State of the Union Message,” New York Times, January 26, 1994, p. A17; “The Clinton Administration Begins,” Foreign Policy Bulletin, Vol. 3, No. 4/5 (Jan-Apr 1993. p.5

http://www.cfr.org/publication/10647/group_of_eight_g8_industrialized_nations.html?breadcrumb=%2Fissue%2Fpublication_list%3Fid%3D23#3 Accessed 30 March, 2007

http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills accessed 30 March 2007. R.J. Rummel with Edward J.H. Udell

Jervis, Robert, Rational Deterrence: Theory and Evidence (World Politics, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Jan., 1989), pp. 183-207)

Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace (The Library of Liberal Arts, published by, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis – New York)

MacMillan, John, Beyond the Separate Democratic Peace (Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 40, No. 2, March 2003)

Murray, W., Macgregor, K., Bernstein, A., (eds.) The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States and War (Cambridge University Press) Gray, Colin, S., Chapter 18, Strategy in the Nuclear Age: The United States, 1945-1991

Owen, John M., How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace, International Security, 19(2)

Owen, John M., Iraq and the Democratic Peace (Foreign Affairs, Nov/Dec 2005)

Rosato, Sebastian, University of Chicago, The Flawed Logic of Democratic Peace Theory (American Political Science Review, Vol. 97, No. 4, Nov. 2003

[1]http://www.cfr.org/publication/10647/group_of_eight_g8_industrialized_nations.html?breadcrumb=%2Fissue%2Fpublication_list%3Fid%3D23#3 Accessed 30 March, 2007

[2]http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills accessed 30 March 2007. R.J. Rummel with Edward J.H. Udell

[3] Clausewitz, C., On War (Ware, Hertfordshire, Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1997), p.1

[4] “Excerpts from President Clintons State of the Union Message,” New York Times, January 26, 1994, p. A17; “The Clinton Administration Begins,” Foreign Policy Bulletin, Vol. 3, No. 4/5 (Jan-Apr 1993. p.5

[5] http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills accessed 30 March 2007. R.J. Rummel with Edward J.H. Udell

[6] Owen, John M., How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace, International Security, 19(2), p. 90

[7] ibid. p.95

[8] MacMillan, J., Beyond the Separate Democratic Peace (Journal of Peace Research. Vol. 40, No. 2, March 2003, footnote 2) p. 233

[9] Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace (The Library of Liberal Arts, published by, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis – New York) p. 32

[10] Skinner, Q., Machiavelli – A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000), p.58

[11] Chakma, B., University of Hull, The Nature of War Lecture: War Decision; The Peloponnesian War and the Cuban Missile Crisis, Lecture 2, slide 5, 14 Feb. 2007

[12] Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace (The Library of Liberal Arts, published by, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis – New York) p. 51

[13] MacMillan, J., Beyond the Separate Democratic Peace (Journal of Peace Research. Vol. 40, No. 2, March 2003, footnote 2) p. 234

[14] ibid. 233

[15] Magone, J., University of Hull, States in the New International Order Lecture: From the USSR to Russia; Democratisation and Economic Liberalisation, Lecture Five, Slide 38, 2 Mar 2007

[16]Owen, John M., How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace, International Security, 19(2), p.86

[17] Murray, W., Macgregor, K., Bernstein, A., (eds.) The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States and War (Cambridge University Press) Gray, Colin, S., Chapter 18, Strategy in the Nuclear Age: The United States, 1945-1991, p. 591

This could be considered one of the most important questions of our time. Consequently, if there is a working formula or theory that will answer this question in the affirmative, it could provide like minded nations of the world and their leaders a resource, coupled with the motivation and governance necessary to share their combined knowledge and strength (using other successful states as their examples and providing justification) as a model to empower those not presently participating in democracy to join them with confidence and authority in uniting with the community of non-belligerent states. If taken to its end, it could inevitably go a long way towards eradicating war from the face of the earth.

The object of this report will be to support the theory that major war has become obsolete, while explaining the key terms in context to the question presented, and use historical events and information from experts, as a foundation to support this conclusion.

In order to build a foundation for the above assertion and provide cognizant evidence in support of this declaration, it will be necessary to define the critical aspects of the usage of particular verbiage contained in the initial question.

First-of-all, an ‘Industrialised Nation’, will be considered as a member of the ‘G8’, or ‘First World’ democracy, and for the purposes of brevity and example will include, as defined by the Council on Foreign Relations as; the United States of America, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, Canada and Russia[1]. The preceding states will be the focus of this report.

Secondly, Democracy or ‘Liberal Democracy’ in its broadest sense will be, for the most part, defined as states since 1945 that have the following criteria: (1) a government by the people, either directly or through elected representatives; (2) Modern, including a Universal Franchise, Secret Ballot, and Regular and Competitive Elections; (3) Liberal, Electoral, including Freedom of Speech, Religion, association and Rule by Law; (4) Historical, at least 2/3 of the adult male population can vote; (5) Competitive Elections, for Legislature and Executive and (5), at least one Transfer of Power.[2]

Thirdly, in an attempt to keep things direct and to the point for the purposes of this particular paper, one of Clausewitz’s definitions of war will be used in context to the essay question, namely, “War is nothing but a duel on an extensive scale.”[3]

Therefore, why is major war obsolete, or out of date, today? To answer this question, three situations will be looked at as support for the answer to the question. Firstly, democracies do not fight each other. Secondly, democratic states that are economically dependant upon one another do not go to war, and finally, democratic states that are ideologically bound by norms and institutions work together rather than fight one another.

In support of the first assumption that democracies do not fight each other, a quote from President Bill Clinton in his 1994 State of the Union address seems fitting, “Democracies do not attack each other…ultimately the best strategy to insure our security and to build a durable peace is to support the advance of democracy elsewhere.”[4] Since the end of World War II, and especially the fall of communism, democracy has taken hold all over the globe. For example, as of 2004, there were over one hundred democracies in the world.[5] Since there is extensive evidence to support the theory that democracies do not go to war with one another, and since the trend for states throughout the world since WWII to move towards democracy has dramatically increased, the probability of war between democracies will by default become more obsolete, or out of date as more and more non-democracies join the community of democratic states throughout the world.

Another explanation to support the conclusion supporting the democratic peace theory needs to be explored here. To quote John M. Owen, who explains two key theories of democratic peace, and why they work,

Structural accounts attribute the democratic peace to the institutional constraints within democracies. Chief executives in democracies must gain approval for war from cabinet member or legislatures, and ultimately from the electorate. Normative theory (italics added) locates the cause of the democratic peace in the ideas or norms held by democracies. Democracies believe it would be unjust or imprudent to fight one another. They practice the norm of compromise with each other that works so well within their own borders.[6]

In a democracy, the will of the people is paramount. Free citizens will naturally not vote

for war because they will not only be bearing the economic cost, through taxation, etc., they will be sending their own children to fight the actual battle.[7] In other words the cost is too high. Therefore, if all states in the world were democratic, people would vote to not fight, and thus war would become obsolete. Although not within the scope of this report, it is worth briefly mentioning that although there is strong evidence supporting peace between democracies, there is also a progressive philosophy, which theorises that as non-democratic states apply democratic ideals into their respective systems and as democratic peace initiatives mature, war between liberal states and illiberal ones become less likely as well. MacMillan elaborates on this theorem. He states, “…the balance of evidence and argument supports a shift from the conventional ‘separate democratic peace’ position that liberal states are peace prone only in relations with other liberal states to the view that they are also more peace prone in relations with non-liberal states than usually thought.”[8]

Secondly, democratic states that are economically dependent upon one another do not go to war. In speaking about perpetual peace as it relates to international law, Kant says, “The spirit of commerce, which is incompatible with war, sooner or later gains the upper hand in every state.”[9] Therefore, democracy inherently encourages an entrepreneurial spirit, which in the end, results in strong economies, full treasuries and economic stability, increasing the chance for even more stability as time goes on.[10] With the increased receipts going into a governments treasury, it is able to fund programs, build infrastructures, strengthen education, health care, and welfare, which will continue to help move a society even further away from a desire for war, because the society is content to maintain this status quo and do nothing that would risk upsetting it. In quoting Dr. Bhumitra Chakma, “According to Plato, war is less likely where the population is cohesive and enjoy a moderate level of prosperity.” He goes on to say, “wealthy masses are satisfied with the status quo (hence war is less likely).”[11] The need for war to secure economic prosperity and stability, especially within the context of the industrialised democracies, is not necessary and therefore the combination of liberal democratic ideals and economic growth within democracies over time will make war obsolete within the participating regimes.

And thirdly, democratic states that are ideologically bound by norms and institutions work together, for the most part, rather than fight one another. Speaking of the moral strength democracies gain by banning together in what he calls a ‘federation’, Kant states,

We have seen that a federation of states, which has for its sole purpose the maintenance of peace, is the only juridical condition compatible with the freedom of the several states. Therefore the harmony of politics with morals is possible only in a federative alliance, and the latter is necessary and given a priori by the principle of right. [12]

Incorporating Kant’s federation of states idea with economic interdependence, it has been shown that as economies in and between democratic states become more and more interdependent, the likelihood of war between these states is reduced dramatically. For example, institutions such as NAFTA and the EU have increased economic ties through their alliances and because of this, the likelihood of major war between even historical enemies such as France and Germany seems to have been eliminated. In an article written in the Journal of Peace Research, by John Macmillan, quoting Russet and O’Neal, they state,

The inter-relationships between democratic states, economic interactions and membership of international organisations can generate ‘virtuous circles’ that lead to greater levels of peace in international relations…they also find that international trade and membership in international organizations correlate positively with the probability of a state being at peace.[13]

As with many theories and ideas, there are always unforeseen possibilities or circumstances that can be categorized as exceptions to the rule. One of these possibilities needs to be explained at this point, and that is what Owen calls ‘perception’. In other words, even though a state considers or calls itself a liberal democracy, for example, doesn’t necessarily mean that other states believe the same. Owen states concerning the importance of perceptions,

That a state has enlightened citizens and liberal-democratic institutions, however, is not sufficient for it to belong to the democratic peace: if its peer states do not believe it is a liberal democracy, they will not treat it as one…for the liberal mechanism to prevent a liberal democracy from going to war against a foreign state, liberals must consider the foreign state a liberal democracy.[14]

An example of a state that could fall into this category at present is Russia. A lecture given by Dr. Jose M. Magone points out several factors that could cause one liberal democracy to question another liberal democracies level of ‘true’ liberal democratisation. In his conclusion, he gives five examples that show this, namely; Russia has experienced a turbulent transition to democracy, its autocratic past is still affecting the politics of Russia, and it has a strong presidential system with tendencies towards abuse, weak political parties, some of them very close to power and a fragile economy, in spite of recent spectacular growth.[15]

Because industrialised democracies have so much more to lose than gain by getting involved in a major war with one another in most circumstances, not to mention the great potential for human and economic loss, the likelihood of war between them is very low. For example, between 1952 and 1980 countries throughout the world that were considered democracies engaged in war with one another a total of zero times.[16]

In conclusion, the reasons industrial democracies do not fight wars with each other is because they encourage free trade with one another therefore becoming economically dependant upon one another and by their very nature as democracies see each another as partners that are ideologically bound by norms and institutions that are common in their political and cultural environments. It must also be noted that the very fact that the United States of America, with its military hegemonic might and superpower status, is a great help in forwarding and supporting the worlds move to democracy. With its society firmly behind the American idea that liberal democracy needs to be spread throughout the world, other democratic states everywhere will have the confidence and proxy-authority to do the same. Colin S. Gray, in The Making of Strategy says,

American society is deeply convinced that the world is destined to be governed by the precepts of American liberal democracy. Some influential Americans have taken the Soviet collapse as proof of the superiority of American ideas on good governance and enlightened economics over those of the forces of darkness and evil.[17]

With many new developing democracies maturing throughout the world at present, the future for peace could be said to have never been better than at this moment in time. As stated in this paper, as long as these states follow the example of true liberal democracy and apply its ideals of economic interdependence, and ideologically bind themselves together by implementing established democratic norms and institutions, eventual worldwide peace may be within reach.

In the spirit of the Kantian philosophy, freedom in all its forms may be the only sure way to secure long-term peace and security in a world that seems to be longing for more of it.

Anson D. Bentley

Bibliography

BBC News, Do Democracies Fight Each Other? -

http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk/mpapps/pagetools/print/news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/4017305.stm%20accessed%2030%20March%202007

Clausewitz, C., On War (Ware, Hertfordshire, Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1997)

“Excerpts from President Clintons State of the Union Message,” New York Times, January 26, 1994, p. A17; “The Clinton Administration Begins,” Foreign Policy Bulletin, Vol. 3, No. 4/5 (Jan-Apr 1993. p.5

http://www.cfr.org/publication/10647/group_of_eight_g8_industrialized_nations.html?breadcrumb=%2Fissue%2Fpublication_list%3Fid%3D23#3 Accessed 30 March, 2007

http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills accessed 30 March 2007. R.J. Rummel with Edward J.H. Udell

Jervis, Robert, Rational Deterrence: Theory and Evidence (World Politics, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Jan., 1989), pp. 183-207)

Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace (The Library of Liberal Arts, published by, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis – New York)

MacMillan, John, Beyond the Separate Democratic Peace (Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 40, No. 2, March 2003)

Murray, W., Macgregor, K., Bernstein, A., (eds.) The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States and War (Cambridge University Press) Gray, Colin, S., Chapter 18, Strategy in the Nuclear Age: The United States, 1945-1991

Owen, John M., How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace, International Security, 19(2)

Owen, John M., Iraq and the Democratic Peace (Foreign Affairs, Nov/Dec 2005)

Rosato, Sebastian, University of Chicago, The Flawed Logic of Democratic Peace Theory (American Political Science Review, Vol. 97, No. 4, Nov. 2003

[1]http://www.cfr.org/publication/10647/group_of_eight_g8_industrialized_nations.html?breadcrumb=%2Fissue%2Fpublication_list%3Fid%3D23#3 Accessed 30 March, 2007

[2]http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills accessed 30 March 2007. R.J. Rummel with Edward J.H. Udell

[3] Clausewitz, C., On War (Ware, Hertfordshire, Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1997), p.1

[4] “Excerpts from President Clintons State of the Union Message,” New York Times, January 26, 1994, p. A17; “The Clinton Administration Begins,” Foreign Policy Bulletin, Vol. 3, No. 4/5 (Jan-Apr 1993. p.5

[5] http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills accessed 30 March 2007. R.J. Rummel with Edward J.H. Udell

[6] Owen, John M., How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace, International Security, 19(2), p. 90

[7] ibid. p.95

[8] MacMillan, J., Beyond the Separate Democratic Peace (Journal of Peace Research. Vol. 40, No. 2, March 2003, footnote 2) p. 233

[9] Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace (The Library of Liberal Arts, published by, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis – New York) p. 32

[10] Skinner, Q., Machiavelli – A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000), p.58

[11] Chakma, B., University of Hull, The Nature of War Lecture: War Decision; The Peloponnesian War and the Cuban Missile Crisis, Lecture 2, slide 5, 14 Feb. 2007

[12] Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace (The Library of Liberal Arts, published by, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis – New York) p. 51

[13] MacMillan, J., Beyond the Separate Democratic Peace (Journal of Peace Research. Vol. 40, No. 2, March 2003, footnote 2) p. 234

[14] ibid. 233

[15] Magone, J., University of Hull, States in the New International Order Lecture: From the USSR to Russia; Democratisation and Economic Liberalisation, Lecture Five, Slide 38, 2 Mar 2007

[16]Owen, John M., How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace, International Security, 19(2), p.86

[17] Murray, W., Macgregor, K., Bernstein, A., (eds.) The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States and War (Cambridge University Press) Gray, Colin, S., Chapter 18, Strategy in the Nuclear Age: The United States, 1945-1991, p. 591

Acheivements of the Third Wave of Democracy

For the purposes of setting a standard for this report, it would be appropriate to start with a definition of a wave of democratisation. Samuel P. Huntington defines a wave as; “a group of transitions from nondemocratic to democratic regimes that occurs within a specific period and that significantly outnumbers transitions in the opposite direction in the same period.”[1] As quoted in Comparative Politics Today, Samuel P. Huntington speaks of the recent move towards democracy as a “Third Wave” of worldwide democratisation.[2] This ‘Third Wave’ of democratisation could be considered the most important and influential process to further the cause of inalienable rights of human beings throughout the world in modern times. This “global democratic revolution” is probably the most important political trend in the late twentieth century”, says Huntington.[3] In just over thirty years, it has spread around the globe to places that would never have conceived or dreamed of democracy in their nations only a few years ago. Huntington goes on to say, as quoted in Political Science Quarterly, speaking of the ‘Third Wave’, “Between 1974 and 1990, more than thirty countries in Southern Europe, Latin America, East Asia and Eastern Europe shifted from authoritarian to democratic systems of government.”[4] This paper will look at several of the achievements of the ‘Third Wave’, and show how they have brought peace, prosperity and freedom to nations in all four corners of the world.

First-of-all, one of the main initial achievements was the end of right wing dictatorships in Southern Europe, namely Greece, Portugal and Spain in the early 1970’s. This not only brought democracy to these nations, it is considered to be the beginning of the ‘Third Wave’. Secondly, much of Latin America, in the 1980’s ousted their dictators and embraced democratic forms of government in their respective countries. And thirdly, the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe at the end of the 1980’s was a change nobody saw coming.[5] Using democratisation as the principle achievement of the ‘Third Wave’, this paper will look at the underlying achievements that are associated with democratisation as well.

Writing in the American Political Science Review, Michael Ward and Kristian Gleditsch, find that there is a direct correlation between democratisation and the decreased probability of war. They state,

Do polities become more peaceful as they democratise? Alternatively, is political change toward greater political democracy associated with increased likelihood of war? Research following Babst’s (1964) observation of an apparent absence of a war between democracies has produced considerable empirical evidence for the liberal proposition (Kant [1795] 1991) that democracies rarely if ever fight one another. Our findings demonstrate that democratising polities are substantially less war prone than previously argued…we show that as contemporary polities become more democratic, they reduce their overall chances of being involved in war by approximately half…both in the long term and while societies undergo democratic change, the risks of war are reduced by democratisation.[6]

The decrease in the probability of war could be said to be the greatest achievement of democratisation.

Another achievement came about because of the tremendous growth of democratisation since 1974. Systems needed to be put in place to support this growth to empower democracies and give them the necessary level of assistance so that they could have the best chance to progress and succeed. Subsequently international democracy assistance became a growth industry and several institutions involved in supporting electoral processes and institution building were developed. Organisations like the United Nations Development program, German foundations such as, the Friedrich Ebert foundation, the Konrad Adenauer foundation along with many others involved in democracy assistance, like the National Endowment for Democracy, the Carnegie and Ford foundations.[7] These organisations will most likely remain active permanently and be available to assist more governments as they join the community of democratised nations, insuring their best chance of building a foundation that will help develop democratisation efforts in their respective nations.

A by-product of democratisation has been the external pressure that has been placed upon non-democratic nations of the world by default to relax uncivilised human rights practices and allow for more personal freedoms and privileges to their subjects, because of the fear of mass rebellion, which open information systems may facilitate. The fact that modern day communications, especially the internet, allow information to be transferred at light speed around the world, citizens of the world, wherever they may be have a much greater probability of learning about how the rest of the democratised world lives and the human rights and economic opportunities that they enjoy. Also, it has become much more difficult for propaganda regimes in these nations to deceive their populations.[8] For example, in China, despite all the governments efforts to suppress and regulate information, “internet access is expanding rapidly…allowing a sophisticated minority to circumvent the parties attempt to restrict full information to its own elite.”[9] Almond goes on to say, “Around the world, political change has created in the late twentieth century an age of democratisation…with reform, for most ordinary Chinese, the party has demanded less and delivered more in recent decades.”[10]

A great result and achievement of democratisation are the increase of free, fair and competitive elections in newly democratised states. Although the challenges of political participation in new democracies is considerable, states including South Africa, most of Eastern Europe and Africa have made it through their founding elections successfully. Although their subsequent elections have not seen the high-turnout experienced in initial elections, signs that these democracies are beginning to stabilise and mature are evident.[11] Harrop and Hague elaborate,

Certainly, elections in some new democracies have acquired the routine character that reflects consolidation of the democratic order. When the election itself ceases to be the issue, and the focus shifts instead to the competing parties, elections have become an institutionalised part of an established democracy. In these circumstances, a decline in turnout may even indicate a maturing democracy.[12]

Democratisation has been a champion of individual rights as it has spread throughout the world. It naturally promotes personal freedoms that have been deemed inalienable by default. Rights such as freedom of speech, religion, the press, assembly and equal protection under the law are the lifeblood of any democracy. Individual rights have been expanded during the ‘Third Wave’, more than at anytime in history. The momentum that has been created because of this expansion will likely be a catalyst in helping non-democratised states that are on the brink of conversion to democratise.

The ‘Third Wave’ has progressed the idea that democracy itself is a human right. Instilled in the ideology of the principles of democracy is that all are created equal. If one group for example has the right to live in a free society, then so does the other. Larry Diamond in an article written for The Hoover Institution stated,

Finally, then, what has changed during the third wave is the normative weight given to human rights – and to democracy as a human right – in international discourse, treaties law and collective actions. The world community is increasingly embracing a shared normative expectation that all states seeking international legitimacy should manifestly “govern with the consent of the governed” – in essence, a “right to democratic governance” is seen as a legal entitlement…at a minimum, this evolution has done two things. First, it has lowered the political threshold for intervention, not only for the multilateral actors but for states and NGOs as well. Second, it has emboldened domestic advocates of democracy and human rights. No factor has been more important in driving and sustaining the third wave of democratisation than the cluster of international normative and legal trends.[13]

Economic development has been a major achievement of democratisation. Without a strong economy, even the best-intentioned society will find it very difficult to provide even the bare necessities required to build communities and maintain essential infrastructure. If the economy can sustain these basics, democracy has an excellent chance of building a foundation and developing into a strong and vibrant democracy. Concerning economic development, Larry Diamond went on to say,

As Huntington notes, economic development has been a major driver of democratisation in the third wave. However, increases in national wealth bring about pressures for democratisation only to the extent that they generate several other intervening effects: rising levels of education; the creation of a complex and diverse middle class that is independent of the state; the development of a more pluralistic, active, and resourceful civil society; and, as a result of all these changes, the emergence of a more questioning, assertive, pro-democratic culture.

These broad societal transformations have accompanied economic development in a number of countries in recent decades. South Korea and Taiwan stand as the classic examples of economic growth bringing about diffuse, social, economic and cultural change that then generates diffuse societal pressure for democracy.[14]

In conclusion, the achievements of the ‘Third Wave of Democratisation’ have not guaranteed anything, but have allowed nations and individuals the right to live free, under the rule of law and pursue their dreams much more than they have been able to do so in the past under former authoritarian regimes. Although many of the new democracies have a long way to go in their pursuit of full democracy, the door has been opened and the opportunity and much of the needed infrastructure is available for support more now than at anytime in the past. Larry Diamond states,

In Short, the international context has never mattered more to the future of democracy or been more favourable. We are on the cusp of a grand historical tipping point, when a visionary and resourceful strategy could – if it garnered the necessary cooperation and effort among the powerful democracies – essentially eliminate authoritarian rule over the next generation or two.[15]

As the ‘Third Wave of Democratisation” spreads throughout the world and continues to provide examples of success and development, the democratised world community has an opportunity to come together that they may share what they have received with those nations who are looking for a way to join the world community of free states.

…democracy will continue to spread and expand in the world. History has proven that it is the best form of government. Gradually, more countries will become democratic while fewer revert to dictatorship. If we retain our power, reshape our strategy, and sustain our commitment, eventually – not in the next decade, but certainly by mid-century – every country in the world can be democratic.[16]

An article written for the US State Department website entitled, ‘What is Democracy’, seems to summarise the ideological achievements of democratisation well,

Democracy itself guarantees nothing. It offers instead the opportunity to succeed as well as the risk of failure. In Thomas Jefferson's ringing but shrewd phrase, the promise of democracy is "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Democracy is then both a promise and a challenge. It is a promise that free human beings, working together, can govern themselves in a manner that will serve their aspirations for personal freedom, economic opportunity, and social justice. It is a challenge because the success of the democratic enterprise rests upon the shoulders of its citizens and no one else. Government of and by the people means that the citizens of a democratic society share in its benefits and in its burdens. By accepting the task of self-government, one generation seeks to preserve the hard-won legacy of individual freedom, human rights, and the rule of law for the next. In each society and each generation, the people must perform the work of democracy anew--taking the principles of the past and applying them to the practices of a new age and a changing society. The late Josef Brodsky, Russian-born poet and Nobel Prize winner, once wrote, "A free man, when he fails, blames nobody." It is true as well for the citizens of democracy who, finally, must take responsibility for the fate of the society in which they themselves have chosen to live.

In the end, we get the government we deserve.[17]

Anson D. Bentley

Bibliography

Almond G., Dalton R., Powell G., Strom K., Comparative Politics Today: A World View, Updated 8th Edition (Pearson Longman, 2006, New York)

Diamond L., Universal Democracy – The Prospect has Never Looked Better, Hoover Institution Policy Review, June & July 2003

Hague R., and Harrop, M., Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction, 6th Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004)

Huntington S., How Countries Democratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991-92

US Department of State, What is Democracy, International Information Programs http://usinfo.state.gov/products/pubs/whatsdem/whatdm8.htm Accessed 11 April 2007

Ward M., Gleditsch K., Democratising for Peace, American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, No.1, March 1988

[1] Huntington S., How Countries Democratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991-92, p. 579

[2] Almond G., Dalton R., Powell G., Strom K., Comparative Politics Today: A World View, Updated 8th Edition (Pearson Longman, 2006, New York), p.28

[3] Huntington S., How Countries Democratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991-92, p. 579

[4] ibid.

[5] Hague R., and Harrop, M., Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction, 6th Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004), p.42

[6] Ward M., Gleditsch K., Democratising for Peace, American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, No.1, March 1988. p.51

[7] Magone, J., States in the New International Order, Lecture Six, Democratisation in the Developing World: The Third Wave, 8 March 2007, pp., 15-16

[8] Hague R., and Harrop, M., Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction, 6th Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004), pp., 105-121

[9] ibid, p. 121

[10] ibid, p. 455

[11] ibid, p. 163

[12] ibid

[13] Diamond L., Universal Democracy – The Prospect has Never Looked Better, Hoover Institution Policy Review, June & July 2003, p. 8&9

[14] ibid, p.7

[15] ibid, pp. 1&2

[16] ibid, pp. 14&15

[17] US Department of State, What is Democracy, International Information Programs http://usinfo.state.gov/products/pubs/whatsdem/whatdm8.htm Accessed 11 April 2007

First-of-all, one of the main initial achievements was the end of right wing dictatorships in Southern Europe, namely Greece, Portugal and Spain in the early 1970’s. This not only brought democracy to these nations, it is considered to be the beginning of the ‘Third Wave’. Secondly, much of Latin America, in the 1980’s ousted their dictators and embraced democratic forms of government in their respective countries. And thirdly, the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe at the end of the 1980’s was a change nobody saw coming.[5] Using democratisation as the principle achievement of the ‘Third Wave’, this paper will look at the underlying achievements that are associated with democratisation as well.

Writing in the American Political Science Review, Michael Ward and Kristian Gleditsch, find that there is a direct correlation between democratisation and the decreased probability of war. They state,

Do polities become more peaceful as they democratise? Alternatively, is political change toward greater political democracy associated with increased likelihood of war? Research following Babst’s (1964) observation of an apparent absence of a war between democracies has produced considerable empirical evidence for the liberal proposition (Kant [1795] 1991) that democracies rarely if ever fight one another. Our findings demonstrate that democratising polities are substantially less war prone than previously argued…we show that as contemporary polities become more democratic, they reduce their overall chances of being involved in war by approximately half…both in the long term and while societies undergo democratic change, the risks of war are reduced by democratisation.[6]

The decrease in the probability of war could be said to be the greatest achievement of democratisation.

Another achievement came about because of the tremendous growth of democratisation since 1974. Systems needed to be put in place to support this growth to empower democracies and give them the necessary level of assistance so that they could have the best chance to progress and succeed. Subsequently international democracy assistance became a growth industry and several institutions involved in supporting electoral processes and institution building were developed. Organisations like the United Nations Development program, German foundations such as, the Friedrich Ebert foundation, the Konrad Adenauer foundation along with many others involved in democracy assistance, like the National Endowment for Democracy, the Carnegie and Ford foundations.[7] These organisations will most likely remain active permanently and be available to assist more governments as they join the community of democratised nations, insuring their best chance of building a foundation that will help develop democratisation efforts in their respective nations.

A by-product of democratisation has been the external pressure that has been placed upon non-democratic nations of the world by default to relax uncivilised human rights practices and allow for more personal freedoms and privileges to their subjects, because of the fear of mass rebellion, which open information systems may facilitate. The fact that modern day communications, especially the internet, allow information to be transferred at light speed around the world, citizens of the world, wherever they may be have a much greater probability of learning about how the rest of the democratised world lives and the human rights and economic opportunities that they enjoy. Also, it has become much more difficult for propaganda regimes in these nations to deceive their populations.[8] For example, in China, despite all the governments efforts to suppress and regulate information, “internet access is expanding rapidly…allowing a sophisticated minority to circumvent the parties attempt to restrict full information to its own elite.”[9] Almond goes on to say, “Around the world, political change has created in the late twentieth century an age of democratisation…with reform, for most ordinary Chinese, the party has demanded less and delivered more in recent decades.”[10]

A great result and achievement of democratisation are the increase of free, fair and competitive elections in newly democratised states. Although the challenges of political participation in new democracies is considerable, states including South Africa, most of Eastern Europe and Africa have made it through their founding elections successfully. Although their subsequent elections have not seen the high-turnout experienced in initial elections, signs that these democracies are beginning to stabilise and mature are evident.[11] Harrop and Hague elaborate,

Certainly, elections in some new democracies have acquired the routine character that reflects consolidation of the democratic order. When the election itself ceases to be the issue, and the focus shifts instead to the competing parties, elections have become an institutionalised part of an established democracy. In these circumstances, a decline in turnout may even indicate a maturing democracy.[12]

Democratisation has been a champion of individual rights as it has spread throughout the world. It naturally promotes personal freedoms that have been deemed inalienable by default. Rights such as freedom of speech, religion, the press, assembly and equal protection under the law are the lifeblood of any democracy. Individual rights have been expanded during the ‘Third Wave’, more than at anytime in history. The momentum that has been created because of this expansion will likely be a catalyst in helping non-democratised states that are on the brink of conversion to democratise.

The ‘Third Wave’ has progressed the idea that democracy itself is a human right. Instilled in the ideology of the principles of democracy is that all are created equal. If one group for example has the right to live in a free society, then so does the other. Larry Diamond in an article written for The Hoover Institution stated,

Finally, then, what has changed during the third wave is the normative weight given to human rights – and to democracy as a human right – in international discourse, treaties law and collective actions. The world community is increasingly embracing a shared normative expectation that all states seeking international legitimacy should manifestly “govern with the consent of the governed” – in essence, a “right to democratic governance” is seen as a legal entitlement…at a minimum, this evolution has done two things. First, it has lowered the political threshold for intervention, not only for the multilateral actors but for states and NGOs as well. Second, it has emboldened domestic advocates of democracy and human rights. No factor has been more important in driving and sustaining the third wave of democratisation than the cluster of international normative and legal trends.[13]

Economic development has been a major achievement of democratisation. Without a strong economy, even the best-intentioned society will find it very difficult to provide even the bare necessities required to build communities and maintain essential infrastructure. If the economy can sustain these basics, democracy has an excellent chance of building a foundation and developing into a strong and vibrant democracy. Concerning economic development, Larry Diamond went on to say,

As Huntington notes, economic development has been a major driver of democratisation in the third wave. However, increases in national wealth bring about pressures for democratisation only to the extent that they generate several other intervening effects: rising levels of education; the creation of a complex and diverse middle class that is independent of the state; the development of a more pluralistic, active, and resourceful civil society; and, as a result of all these changes, the emergence of a more questioning, assertive, pro-democratic culture.

These broad societal transformations have accompanied economic development in a number of countries in recent decades. South Korea and Taiwan stand as the classic examples of economic growth bringing about diffuse, social, economic and cultural change that then generates diffuse societal pressure for democracy.[14]

In conclusion, the achievements of the ‘Third Wave of Democratisation’ have not guaranteed anything, but have allowed nations and individuals the right to live free, under the rule of law and pursue their dreams much more than they have been able to do so in the past under former authoritarian regimes. Although many of the new democracies have a long way to go in their pursuit of full democracy, the door has been opened and the opportunity and much of the needed infrastructure is available for support more now than at anytime in the past. Larry Diamond states,

In Short, the international context has never mattered more to the future of democracy or been more favourable. We are on the cusp of a grand historical tipping point, when a visionary and resourceful strategy could – if it garnered the necessary cooperation and effort among the powerful democracies – essentially eliminate authoritarian rule over the next generation or two.[15]

As the ‘Third Wave of Democratisation” spreads throughout the world and continues to provide examples of success and development, the democratised world community has an opportunity to come together that they may share what they have received with those nations who are looking for a way to join the world community of free states.

…democracy will continue to spread and expand in the world. History has proven that it is the best form of government. Gradually, more countries will become democratic while fewer revert to dictatorship. If we retain our power, reshape our strategy, and sustain our commitment, eventually – not in the next decade, but certainly by mid-century – every country in the world can be democratic.[16]

An article written for the US State Department website entitled, ‘What is Democracy’, seems to summarise the ideological achievements of democratisation well,

Democracy itself guarantees nothing. It offers instead the opportunity to succeed as well as the risk of failure. In Thomas Jefferson's ringing but shrewd phrase, the promise of democracy is "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Democracy is then both a promise and a challenge. It is a promise that free human beings, working together, can govern themselves in a manner that will serve their aspirations for personal freedom, economic opportunity, and social justice. It is a challenge because the success of the democratic enterprise rests upon the shoulders of its citizens and no one else. Government of and by the people means that the citizens of a democratic society share in its benefits and in its burdens. By accepting the task of self-government, one generation seeks to preserve the hard-won legacy of individual freedom, human rights, and the rule of law for the next. In each society and each generation, the people must perform the work of democracy anew--taking the principles of the past and applying them to the practices of a new age and a changing society. The late Josef Brodsky, Russian-born poet and Nobel Prize winner, once wrote, "A free man, when he fails, blames nobody." It is true as well for the citizens of democracy who, finally, must take responsibility for the fate of the society in which they themselves have chosen to live.

In the end, we get the government we deserve.[17]

Anson D. Bentley

Bibliography

Almond G., Dalton R., Powell G., Strom K., Comparative Politics Today: A World View, Updated 8th Edition (Pearson Longman, 2006, New York)

Diamond L., Universal Democracy – The Prospect has Never Looked Better, Hoover Institution Policy Review, June & July 2003

Hague R., and Harrop, M., Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction, 6th Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004)

Huntington S., How Countries Democratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991-92

US Department of State, What is Democracy, International Information Programs http://usinfo.state.gov/products/pubs/whatsdem/whatdm8.htm Accessed 11 April 2007

Ward M., Gleditsch K., Democratising for Peace, American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, No.1, March 1988

[1] Huntington S., How Countries Democratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991-92, p. 579

[2] Almond G., Dalton R., Powell G., Strom K., Comparative Politics Today: A World View, Updated 8th Edition (Pearson Longman, 2006, New York), p.28

[3] Huntington S., How Countries Democratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991-92, p. 579

[4] ibid.

[5] Hague R., and Harrop, M., Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction, 6th Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004), p.42

[6] Ward M., Gleditsch K., Democratising for Peace, American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, No.1, March 1988. p.51

[7] Magone, J., States in the New International Order, Lecture Six, Democratisation in the Developing World: The Third Wave, 8 March 2007, pp., 15-16

[8] Hague R., and Harrop, M., Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction, 6th Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004), pp., 105-121

[9] ibid, p. 121

[10] ibid, p. 455

[11] ibid, p. 163

[12] ibid

[13] Diamond L., Universal Democracy – The Prospect has Never Looked Better, Hoover Institution Policy Review, June & July 2003, p. 8&9

[14] ibid, p.7

[15] ibid, pp. 1&2

[16] ibid, pp. 14&15

[17] US Department of State, What is Democracy, International Information Programs http://usinfo.state.gov/products/pubs/whatsdem/whatdm8.htm Accessed 11 April 2007

Friday 8 June 2007

Prescriptions - Who Pays?

Who should pay the high cost of new drugs: Patients or governments?

Historically, citizens of liberal democratic states who have more of a socialistic point of view when it comes down to the distribution of goods and services to their citizens seem to explain the benefits they are to receive as FREE. I say this to make the point that at the end of the day, the government does not have any resources in and of itself. Resources are supplied to the government by the revenues generated from hard working citizens. Therefore, the citizens, or for this example, patients, will have to pay for the prescriptions either directly, out of their bank account, or indirectly through higher taxes that will be required to pay for the prescriptions, therefore they are not free. To specifically answer the question, the high cost of new drugs must be for the most part paid by the patients themselves, since at the end of the day, they pay directly or indirectly as mentioned above anyway. Also, the government has proven historically to be very inefficient in processing and delivering many services, many times paying well over market value for said products and services, whereas consumers, through the free market system, many times receive much greater value for their money.

However, it is recognized that there is a need for a safety net for those who LEGITIMATELY cannot obtain the medication because of their possible current situation. In these cases, many charities, churches, non profit organizations, extended families, etc. have resources available to help. Once these avenues have been exhausted, it may be necessary to use the resources government has been given, through taxation of the citizenry, to help pay for the drugs.

Historically, citizens of liberal democratic states who have more of a socialistic point of view when it comes down to the distribution of goods and services to their citizens seem to explain the benefits they are to receive as FREE. I say this to make the point that at the end of the day, the government does not have any resources in and of itself. Resources are supplied to the government by the revenues generated from hard working citizens. Therefore, the citizens, or for this example, patients, will have to pay for the prescriptions either directly, out of their bank account, or indirectly through higher taxes that will be required to pay for the prescriptions, therefore they are not free. To specifically answer the question, the high cost of new drugs must be for the most part paid by the patients themselves, since at the end of the day, they pay directly or indirectly as mentioned above anyway. Also, the government has proven historically to be very inefficient in processing and delivering many services, many times paying well over market value for said products and services, whereas consumers, through the free market system, many times receive much greater value for their money.

However, it is recognized that there is a need for a safety net for those who LEGITIMATELY cannot obtain the medication because of their possible current situation. In these cases, many charities, churches, non profit organizations, extended families, etc. have resources available to help. Once these avenues have been exhausted, it may be necessary to use the resources government has been given, through taxation of the citizenry, to help pay for the drugs.

IMMIGRATION

Immigration has become a forefront issue in domestic policy both here in the UK and the USA. With the increased influx of immigrants moving to the UK from eastern europe, the domestic growth of minority groups within the UK and the influx of millions of Mexican citizens migrating (legally or illegally) into the USA, do you think the actual historical demographic will change in the near future for the UK and USA, and what are the consequences?

Thursday 7 June 2007

USA as Lone Superpower, Good or Bad?

Is the world in a better situation today, with the USA as the only superpower, than it was during the cold war? Also, would you rather have another state in this role, and if so, who and why?

G. Brown - for better or worse?

What does everyone think about Gordon Brown? Please comment on each of the below questions, thank you!

- Where does he stand on the political spectrum, far-left, left, center, right, far right?

- Is he for higher or lower overall taxes?

- Larger central government or more local control of gov't?

- Stronger executive powers (ie. prime ministerial powers) or more of a separation of powers approach at the top?

- Environmental activist, passivist or neither?

- On international diplomacy, more US like or more EU like?

- Where do you think he stands on moral issues? (ie. abortion, marriage, death penalty, etc.)

- Education? Any new approaches, or same ole same ole?

These are simply a few general themes to consider, please feel free to comment on anything concerning Gordon Brown and any views you would like to discuss concerning him.

I look forward to the discussion! Many thanks, Anson Bentley

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)