The question ‘Is major war between industrialised democracies obsolete today?’

This could be considered one of the most important questions of our time. Consequently, if there is a working formula or theory that will answer this question in the affirmative, it could provide like minded nations of the world and their leaders a resource, coupled with the motivation and governance necessary to share their combined knowledge and strength (using other successful states as their examples and providing justification) as a model to empower those not presently participating in democracy to join them with confidence and authority in uniting with the community of non-belligerent states. If taken to its end, it could inevitably go a long way towards eradicating war from the face of the earth.

The object of this report will be to support the theory that major war has become obsolete, while explaining the key terms in context to the question presented, and use historical events and information from experts, as a foundation to support this conclusion.

In order to build a foundation for the above assertion and provide cognizant evidence in support of this declaration, it will be necessary to define the critical aspects of the usage of particular verbiage contained in the initial question.

First-of-all, an ‘Industrialised Nation’, will be considered as a member of the ‘G8’, or ‘First World’ democracy, and for the purposes of brevity and example will include, as defined by the Council on Foreign Relations as; the United States of America, France, Germany, Great Britain, Japan, Canada and Russia[1]. The preceding states will be the focus of this report.

Secondly, Democracy or ‘Liberal Democracy’ in its broadest sense will be, for the most part, defined as states since 1945 that have the following criteria: (1) a government by the people, either directly or through elected representatives; (2) Modern, including a Universal Franchise, Secret Ballot, and Regular and Competitive Elections; (3) Liberal, Electoral, including Freedom of Speech, Religion, association and Rule by Law; (4) Historical, at least 2/3 of the adult male population can vote; (5) Competitive Elections, for Legislature and Executive and (5), at least one Transfer of Power.[2]

Thirdly, in an attempt to keep things direct and to the point for the purposes of this particular paper, one of Clausewitz’s definitions of war will be used in context to the essay question, namely, “War is nothing but a duel on an extensive scale.”[3]

Therefore, why is major war obsolete, or out of date, today? To answer this question, three situations will be looked at as support for the answer to the question. Firstly, democracies do not fight each other. Secondly, democratic states that are economically dependant upon one another do not go to war, and finally, democratic states that are ideologically bound by norms and institutions work together rather than fight one another.

In support of the first assumption that democracies do not fight each other, a quote from President Bill Clinton in his 1994 State of the Union address seems fitting, “Democracies do not attack each other…ultimately the best strategy to insure our security and to build a durable peace is to support the advance of democracy elsewhere.”[4] Since the end of World War II, and especially the fall of communism, democracy has taken hold all over the globe. For example, as of 2004, there were over one hundred democracies in the world.[5] Since there is extensive evidence to support the theory that democracies do not go to war with one another, and since the trend for states throughout the world since WWII to move towards democracy has dramatically increased, the probability of war between democracies will by default become more obsolete, or out of date as more and more non-democracies join the community of democratic states throughout the world.

Another explanation to support the conclusion supporting the democratic peace theory needs to be explored here. To quote John M. Owen, who explains two key theories of democratic peace, and why they work,

Structural accounts attribute the democratic peace to the institutional constraints within democracies. Chief executives in democracies must gain approval for war from cabinet member or legislatures, and ultimately from the electorate. Normative theory (italics added) locates the cause of the democratic peace in the ideas or norms held by democracies. Democracies believe it would be unjust or imprudent to fight one another. They practice the norm of compromise with each other that works so well within their own borders.[6]

In a democracy, the will of the people is paramount. Free citizens will naturally not vote

for war because they will not only be bearing the economic cost, through taxation, etc., they will be sending their own children to fight the actual battle.[7] In other words the cost is too high. Therefore, if all states in the world were democratic, people would vote to not fight, and thus war would become obsolete. Although not within the scope of this report, it is worth briefly mentioning that although there is strong evidence supporting peace between democracies, there is also a progressive philosophy, which theorises that as non-democratic states apply democratic ideals into their respective systems and as democratic peace initiatives mature, war between liberal states and illiberal ones become less likely as well. MacMillan elaborates on this theorem. He states, “…the balance of evidence and argument supports a shift from the conventional ‘separate democratic peace’ position that liberal states are peace prone only in relations with other liberal states to the view that they are also more peace prone in relations with non-liberal states than usually thought.”[8]

Secondly, democratic states that are economically dependent upon one another do not go to war. In speaking about perpetual peace as it relates to international law, Kant says, “The spirit of commerce, which is incompatible with war, sooner or later gains the upper hand in every state.”[9] Therefore, democracy inherently encourages an entrepreneurial spirit, which in the end, results in strong economies, full treasuries and economic stability, increasing the chance for even more stability as time goes on.[10] With the increased receipts going into a governments treasury, it is able to fund programs, build infrastructures, strengthen education, health care, and welfare, which will continue to help move a society even further away from a desire for war, because the society is content to maintain this status quo and do nothing that would risk upsetting it. In quoting Dr. Bhumitra Chakma, “According to Plato, war is less likely where the population is cohesive and enjoy a moderate level of prosperity.” He goes on to say, “wealthy masses are satisfied with the status quo (hence war is less likely).”[11] The need for war to secure economic prosperity and stability, especially within the context of the industrialised democracies, is not necessary and therefore the combination of liberal democratic ideals and economic growth within democracies over time will make war obsolete within the participating regimes.

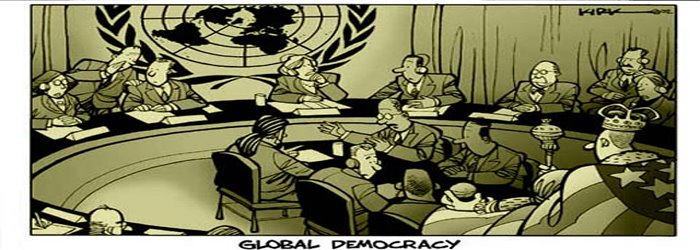

And thirdly, democratic states that are ideologically bound by norms and institutions work together, for the most part, rather than fight one another. Speaking of the moral strength democracies gain by banning together in what he calls a ‘federation’, Kant states,

We have seen that a federation of states, which has for its sole purpose the maintenance of peace, is the only juridical condition compatible with the freedom of the several states. Therefore the harmony of politics with morals is possible only in a federative alliance, and the latter is necessary and given a priori by the principle of right. [12]

Incorporating Kant’s federation of states idea with economic interdependence, it has been shown that as economies in and between democratic states become more and more interdependent, the likelihood of war between these states is reduced dramatically. For example, institutions such as NAFTA and the EU have increased economic ties through their alliances and because of this, the likelihood of major war between even historical enemies such as France and Germany seems to have been eliminated. In an article written in the Journal of Peace Research, by John Macmillan, quoting Russet and O’Neal, they state,

The inter-relationships between democratic states, economic interactions and membership of international organisations can generate ‘virtuous circles’ that lead to greater levels of peace in international relations…they also find that international trade and membership in international organizations correlate positively with the probability of a state being at peace.[13]

As with many theories and ideas, there are always unforeseen possibilities or circumstances that can be categorized as exceptions to the rule. One of these possibilities needs to be explained at this point, and that is what Owen calls ‘perception’. In other words, even though a state considers or calls itself a liberal democracy, for example, doesn’t necessarily mean that other states believe the same. Owen states concerning the importance of perceptions,

That a state has enlightened citizens and liberal-democratic institutions, however, is not sufficient for it to belong to the democratic peace: if its peer states do not believe it is a liberal democracy, they will not treat it as one…for the liberal mechanism to prevent a liberal democracy from going to war against a foreign state, liberals must consider the foreign state a liberal democracy.[14]

An example of a state that could fall into this category at present is Russia. A lecture given by Dr. Jose M. Magone points out several factors that could cause one liberal democracy to question another liberal democracies level of ‘true’ liberal democratisation. In his conclusion, he gives five examples that show this, namely; Russia has experienced a turbulent transition to democracy, its autocratic past is still affecting the politics of Russia, and it has a strong presidential system with tendencies towards abuse, weak political parties, some of them very close to power and a fragile economy, in spite of recent spectacular growth.[15]

Because industrialised democracies have so much more to lose than gain by getting involved in a major war with one another in most circumstances, not to mention the great potential for human and economic loss, the likelihood of war between them is very low. For example, between 1952 and 1980 countries throughout the world that were considered democracies engaged in war with one another a total of zero times.[16]

In conclusion, the reasons industrial democracies do not fight wars with each other is because they encourage free trade with one another therefore becoming economically dependant upon one another and by their very nature as democracies see each another as partners that are ideologically bound by norms and institutions that are common in their political and cultural environments. It must also be noted that the very fact that the United States of America, with its military hegemonic might and superpower status, is a great help in forwarding and supporting the worlds move to democracy. With its society firmly behind the American idea that liberal democracy needs to be spread throughout the world, other democratic states everywhere will have the confidence and proxy-authority to do the same. Colin S. Gray, in The Making of Strategy says,

American society is deeply convinced that the world is destined to be governed by the precepts of American liberal democracy. Some influential Americans have taken the Soviet collapse as proof of the superiority of American ideas on good governance and enlightened economics over those of the forces of darkness and evil.[17]

With many new developing democracies maturing throughout the world at present, the future for peace could be said to have never been better than at this moment in time. As stated in this paper, as long as these states follow the example of true liberal democracy and apply its ideals of economic interdependence, and ideologically bind themselves together by implementing established democratic norms and institutions, eventual worldwide peace may be within reach.

In the spirit of the Kantian philosophy, freedom in all its forms may be the only sure way to secure long-term peace and security in a world that seems to be longing for more of it.

Anson D. Bentley

Bibliography

BBC News, Do Democracies Fight Each Other? -

http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk/mpapps/pagetools/print/news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/magazine/4017305.stm%20accessed%2030%20March%202007

Clausewitz, C., On War (Ware, Hertfordshire, Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1997)

“Excerpts from President Clintons State of the Union Message,” New York Times, January 26, 1994, p. A17; “The Clinton Administration Begins,” Foreign Policy Bulletin, Vol. 3, No. 4/5 (Jan-Apr 1993. p.5

http://www.cfr.org/publication/10647/group_of_eight_g8_industrialized_nations.html?breadcrumb=%2Fissue%2Fpublication_list%3Fid%3D23#3 Accessed 30 March, 2007

http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills accessed 30 March 2007. R.J. Rummel with Edward J.H. Udell

Jervis, Robert, Rational Deterrence: Theory and Evidence (World Politics, Vol. 41, No. 2 (Jan., 1989), pp. 183-207)

Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace (The Library of Liberal Arts, published by, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis – New York)

MacMillan, John, Beyond the Separate Democratic Peace (Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 40, No. 2, March 2003)

Murray, W., Macgregor, K., Bernstein, A., (eds.) The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States and War (Cambridge University Press) Gray, Colin, S., Chapter 18, Strategy in the Nuclear Age: The United States, 1945-1991

Owen, John M., How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace, International Security, 19(2)

Owen, John M., Iraq and the Democratic Peace (Foreign Affairs, Nov/Dec 2005)

Rosato, Sebastian, University of Chicago, The Flawed Logic of Democratic Peace Theory (American Political Science Review, Vol. 97, No. 4, Nov. 2003

[1]http://www.cfr.org/publication/10647/group_of_eight_g8_industrialized_nations.html?breadcrumb=%2Fissue%2Fpublication_list%3Fid%3D23#3 Accessed 30 March, 2007

[2]http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills accessed 30 March 2007. R.J. Rummel with Edward J.H. Udell

[3] Clausewitz, C., On War (Ware, Hertfordshire, Wordsworth Editions Ltd., 1997), p.1

[4] “Excerpts from President Clintons State of the Union Message,” New York Times, January 26, 1994, p. A17; “The Clinton Administration Begins,” Foreign Policy Bulletin, Vol. 3, No. 4/5 (Jan-Apr 1993. p.5

[5] http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills accessed 30 March 2007. R.J. Rummel with Edward J.H. Udell

[6] Owen, John M., How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace, International Security, 19(2), p. 90

[7] ibid. p.95

[8] MacMillan, J., Beyond the Separate Democratic Peace (Journal of Peace Research. Vol. 40, No. 2, March 2003, footnote 2) p. 233

[9] Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace (The Library of Liberal Arts, published by, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis – New York) p. 32

[10] Skinner, Q., Machiavelli – A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000), p.58

[11] Chakma, B., University of Hull, The Nature of War Lecture: War Decision; The Peloponnesian War and the Cuban Missile Crisis, Lecture 2, slide 5, 14 Feb. 2007

[12] Kant, Immanuel, Perpetual Peace (The Library of Liberal Arts, published by, The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc. Indianapolis – New York) p. 51

[13] MacMillan, J., Beyond the Separate Democratic Peace (Journal of Peace Research. Vol. 40, No. 2, March 2003, footnote 2) p. 234

[14] ibid. 233

[15] Magone, J., University of Hull, States in the New International Order Lecture: From the USSR to Russia; Democratisation and Economic Liberalisation, Lecture Five, Slide 38, 2 Mar 2007

[16]Owen, John M., How Liberalism Produces Democratic Peace, International Security, 19(2), p.86

[17] Murray, W., Macgregor, K., Bernstein, A., (eds.) The Making of Strategy: Rulers, States and War (Cambridge University Press) Gray, Colin, S., Chapter 18, Strategy in the Nuclear Age: The United States, 1945-1991, p. 591

FORA.tv Video player

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment