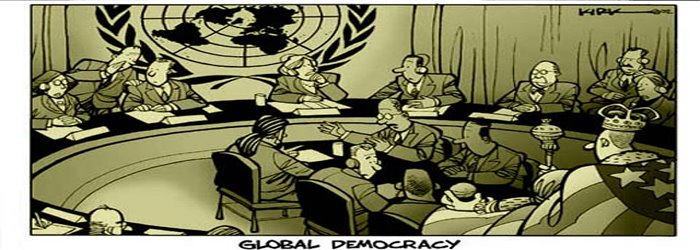

For the purposes of setting a standard for this report, it would be appropriate to start with a definition of a wave of democratisation. Samuel P. Huntington defines a wave as; “a group of transitions from nondemocratic to democratic regimes that occurs within a specific period and that significantly outnumbers transitions in the opposite direction in the same period.”[1] As quoted in Comparative Politics Today, Samuel P. Huntington speaks of the recent move towards democracy as a “Third Wave” of worldwide democratisation.[2] This ‘Third Wave’ of democratisation could be considered the most important and influential process to further the cause of inalienable rights of human beings throughout the world in modern times. This “global democratic revolution” is probably the most important political trend in the late twentieth century”, says Huntington.[3] In just over thirty years, it has spread around the globe to places that would never have conceived or dreamed of democracy in their nations only a few years ago. Huntington goes on to say, as quoted in Political Science Quarterly, speaking of the ‘Third Wave’, “Between 1974 and 1990, more than thirty countries in Southern Europe, Latin America, East Asia and Eastern Europe shifted from authoritarian to democratic systems of government.”[4] This paper will look at several of the achievements of the ‘Third Wave’, and show how they have brought peace, prosperity and freedom to nations in all four corners of the world.

First-of-all, one of the main initial achievements was the end of right wing dictatorships in Southern Europe, namely Greece, Portugal and Spain in the early 1970’s. This not only brought democracy to these nations, it is considered to be the beginning of the ‘Third Wave’. Secondly, much of Latin America, in the 1980’s ousted their dictators and embraced democratic forms of government in their respective countries. And thirdly, the collapse of communism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe at the end of the 1980’s was a change nobody saw coming.[5] Using democratisation as the principle achievement of the ‘Third Wave’, this paper will look at the underlying achievements that are associated with democratisation as well.

Writing in the American Political Science Review, Michael Ward and Kristian Gleditsch, find that there is a direct correlation between democratisation and the decreased probability of war. They state,

Do polities become more peaceful as they democratise? Alternatively, is political change toward greater political democracy associated with increased likelihood of war? Research following Babst’s (1964) observation of an apparent absence of a war between democracies has produced considerable empirical evidence for the liberal proposition (Kant [1795] 1991) that democracies rarely if ever fight one another. Our findings demonstrate that democratising polities are substantially less war prone than previously argued…we show that as contemporary polities become more democratic, they reduce their overall chances of being involved in war by approximately half…both in the long term and while societies undergo democratic change, the risks of war are reduced by democratisation.[6]

The decrease in the probability of war could be said to be the greatest achievement of democratisation.

Another achievement came about because of the tremendous growth of democratisation since 1974. Systems needed to be put in place to support this growth to empower democracies and give them the necessary level of assistance so that they could have the best chance to progress and succeed. Subsequently international democracy assistance became a growth industry and several institutions involved in supporting electoral processes and institution building were developed. Organisations like the United Nations Development program, German foundations such as, the Friedrich Ebert foundation, the Konrad Adenauer foundation along with many others involved in democracy assistance, like the National Endowment for Democracy, the Carnegie and Ford foundations.[7] These organisations will most likely remain active permanently and be available to assist more governments as they join the community of democratised nations, insuring their best chance of building a foundation that will help develop democratisation efforts in their respective nations.

A by-product of democratisation has been the external pressure that has been placed upon non-democratic nations of the world by default to relax uncivilised human rights practices and allow for more personal freedoms and privileges to their subjects, because of the fear of mass rebellion, which open information systems may facilitate. The fact that modern day communications, especially the internet, allow information to be transferred at light speed around the world, citizens of the world, wherever they may be have a much greater probability of learning about how the rest of the democratised world lives and the human rights and economic opportunities that they enjoy. Also, it has become much more difficult for propaganda regimes in these nations to deceive their populations.[8] For example, in China, despite all the governments efforts to suppress and regulate information, “internet access is expanding rapidly…allowing a sophisticated minority to circumvent the parties attempt to restrict full information to its own elite.”[9] Almond goes on to say, “Around the world, political change has created in the late twentieth century an age of democratisation…with reform, for most ordinary Chinese, the party has demanded less and delivered more in recent decades.”[10]

A great result and achievement of democratisation are the increase of free, fair and competitive elections in newly democratised states. Although the challenges of political participation in new democracies is considerable, states including South Africa, most of Eastern Europe and Africa have made it through their founding elections successfully. Although their subsequent elections have not seen the high-turnout experienced in initial elections, signs that these democracies are beginning to stabilise and mature are evident.[11] Harrop and Hague elaborate,

Certainly, elections in some new democracies have acquired the routine character that reflects consolidation of the democratic order. When the election itself ceases to be the issue, and the focus shifts instead to the competing parties, elections have become an institutionalised part of an established democracy. In these circumstances, a decline in turnout may even indicate a maturing democracy.[12]

Democratisation has been a champion of individual rights as it has spread throughout the world. It naturally promotes personal freedoms that have been deemed inalienable by default. Rights such as freedom of speech, religion, the press, assembly and equal protection under the law are the lifeblood of any democracy. Individual rights have been expanded during the ‘Third Wave’, more than at anytime in history. The momentum that has been created because of this expansion will likely be a catalyst in helping non-democratised states that are on the brink of conversion to democratise.

The ‘Third Wave’ has progressed the idea that democracy itself is a human right. Instilled in the ideology of the principles of democracy is that all are created equal. If one group for example has the right to live in a free society, then so does the other. Larry Diamond in an article written for The Hoover Institution stated,

Finally, then, what has changed during the third wave is the normative weight given to human rights – and to democracy as a human right – in international discourse, treaties law and collective actions. The world community is increasingly embracing a shared normative expectation that all states seeking international legitimacy should manifestly “govern with the consent of the governed” – in essence, a “right to democratic governance” is seen as a legal entitlement…at a minimum, this evolution has done two things. First, it has lowered the political threshold for intervention, not only for the multilateral actors but for states and NGOs as well. Second, it has emboldened domestic advocates of democracy and human rights. No factor has been more important in driving and sustaining the third wave of democratisation than the cluster of international normative and legal trends.[13]

Economic development has been a major achievement of democratisation. Without a strong economy, even the best-intentioned society will find it very difficult to provide even the bare necessities required to build communities and maintain essential infrastructure. If the economy can sustain these basics, democracy has an excellent chance of building a foundation and developing into a strong and vibrant democracy. Concerning economic development, Larry Diamond went on to say,

As Huntington notes, economic development has been a major driver of democratisation in the third wave. However, increases in national wealth bring about pressures for democratisation only to the extent that they generate several other intervening effects: rising levels of education; the creation of a complex and diverse middle class that is independent of the state; the development of a more pluralistic, active, and resourceful civil society; and, as a result of all these changes, the emergence of a more questioning, assertive, pro-democratic culture.

These broad societal transformations have accompanied economic development in a number of countries in recent decades. South Korea and Taiwan stand as the classic examples of economic growth bringing about diffuse, social, economic and cultural change that then generates diffuse societal pressure for democracy.[14]

In conclusion, the achievements of the ‘Third Wave of Democratisation’ have not guaranteed anything, but have allowed nations and individuals the right to live free, under the rule of law and pursue their dreams much more than they have been able to do so in the past under former authoritarian regimes. Although many of the new democracies have a long way to go in their pursuit of full democracy, the door has been opened and the opportunity and much of the needed infrastructure is available for support more now than at anytime in the past. Larry Diamond states,

In Short, the international context has never mattered more to the future of democracy or been more favourable. We are on the cusp of a grand historical tipping point, when a visionary and resourceful strategy could – if it garnered the necessary cooperation and effort among the powerful democracies – essentially eliminate authoritarian rule over the next generation or two.[15]

As the ‘Third Wave of Democratisation” spreads throughout the world and continues to provide examples of success and development, the democratised world community has an opportunity to come together that they may share what they have received with those nations who are looking for a way to join the world community of free states.

…democracy will continue to spread and expand in the world. History has proven that it is the best form of government. Gradually, more countries will become democratic while fewer revert to dictatorship. If we retain our power, reshape our strategy, and sustain our commitment, eventually – not in the next decade, but certainly by mid-century – every country in the world can be democratic.[16]

An article written for the US State Department website entitled, ‘What is Democracy’, seems to summarise the ideological achievements of democratisation well,

Democracy itself guarantees nothing. It offers instead the opportunity to succeed as well as the risk of failure. In Thomas Jefferson's ringing but shrewd phrase, the promise of democracy is "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness." Democracy is then both a promise and a challenge. It is a promise that free human beings, working together, can govern themselves in a manner that will serve their aspirations for personal freedom, economic opportunity, and social justice. It is a challenge because the success of the democratic enterprise rests upon the shoulders of its citizens and no one else. Government of and by the people means that the citizens of a democratic society share in its benefits and in its burdens. By accepting the task of self-government, one generation seeks to preserve the hard-won legacy of individual freedom, human rights, and the rule of law for the next. In each society and each generation, the people must perform the work of democracy anew--taking the principles of the past and applying them to the practices of a new age and a changing society. The late Josef Brodsky, Russian-born poet and Nobel Prize winner, once wrote, "A free man, when he fails, blames nobody." It is true as well for the citizens of democracy who, finally, must take responsibility for the fate of the society in which they themselves have chosen to live.

In the end, we get the government we deserve.[17]

Anson D. Bentley

Bibliography

Almond G., Dalton R., Powell G., Strom K., Comparative Politics Today: A World View, Updated 8th Edition (Pearson Longman, 2006, New York)

Diamond L., Universal Democracy – The Prospect has Never Looked Better, Hoover Institution Policy Review, June & July 2003

Hague R., and Harrop, M., Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction, 6th Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004)

Huntington S., How Countries Democratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991-92

US Department of State, What is Democracy, International Information Programs http://usinfo.state.gov/products/pubs/whatsdem/whatdm8.htm Accessed 11 April 2007

Ward M., Gleditsch K., Democratising for Peace, American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, No.1, March 1988

[1] Huntington S., How Countries Democratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991-92, p. 579

[2] Almond G., Dalton R., Powell G., Strom K., Comparative Politics Today: A World View, Updated 8th Edition (Pearson Longman, 2006, New York), p.28

[3] Huntington S., How Countries Democratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 106, No. 4, 1991-92, p. 579

[4] ibid.

[5] Hague R., and Harrop, M., Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction, 6th Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004), p.42

[6] Ward M., Gleditsch K., Democratising for Peace, American Political Science Review, Vol. 92, No.1, March 1988. p.51

[7] Magone, J., States in the New International Order, Lecture Six, Democratisation in the Developing World: The Third Wave, 8 March 2007, pp., 15-16

[8] Hague R., and Harrop, M., Comparative Government and Politics, an Introduction, 6th Edition (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004), pp., 105-121

[9] ibid, p. 121

[10] ibid, p. 455

[11] ibid, p. 163

[12] ibid

[13] Diamond L., Universal Democracy – The Prospect has Never Looked Better, Hoover Institution Policy Review, June & July 2003, p. 8&9

[14] ibid, p.7

[15] ibid, pp. 1&2

[16] ibid, pp. 14&15

[17] US Department of State, What is Democracy, International Information Programs http://usinfo.state.gov/products/pubs/whatsdem/whatdm8.htm Accessed 11 April 2007

FORA.tv Video player

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment